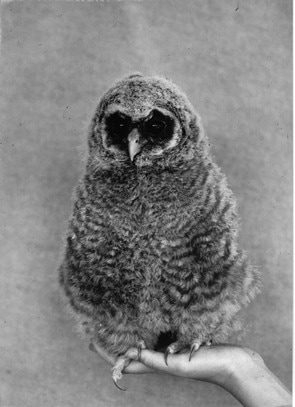

In the spring of 1970 Spotted Owl biologist Eric Forsman saw a Spotted Owl fly into a cavity high up in an old-growth Douglas-fir in the Coast Ranges just west of Philomath, Oregon. Since at the time this would have been only the second Spotted Owl nest ever found in Oregon, Eric climbed the tree to investigate. As he headed up the tree he was attacked by the adult owls, both of which raked him repeatedly with their talons, leaving scratches all over the back of his head, and a long scratch across the side of his face that just missed his eye. When he reached the nest, he found two fluffy owlets inside that were about three weeks old. They had been bitten so badly by parasitic flies that their eyes were completely glued shut with blood. Eric removed one of them from the nest to treat its eye problem. When he returned to put it back in the nest the next day, the other chick had been killed by a predator and the adults were gone. Eric considered putting the owlet back in the nest to see if the adults would return to take care of it, but decided instead that it would be better to raise it in captivity and use it as an exhibition bird when he gave talks to educate people about Spotted Owls. As Eric drove home that day he had no idea that this was the beginning of a 32-year odyssey during which that little ball of fluff in the box in the back seat would become his constant companion, as well as an ambassador for her species.

Due to the owlet's tendency toward overeating and obesity, one of Eric's friends commented one day "She looks just like the character they call Fat Broad in the BC comic strip". The name stuck, and the political incorrectness of her name never bothered her.

Fat Broad rapidly became part of Eric's family, as well as an important source of information on the biology of the Spotted Owl. She lived in a large cage beside the Forsman house, and for years Eric kept notes on her molt and her behavior. These observations led Eric to publish papers on the molt, behavior, and nesting chronology of the Spotted Owl. But much more importantly, she traveled with Eric to numerous public presentations and visits to schools when he gave talks about Spotted Owls and old forests. At these talks Eric frequently let her loose to roam around the room. She was a great addition to the programs because regardless of whether Eric gave a good presentation or not, people in the audience were always in awe of the beautiful brown owl that was completely at ease in the middle of the crowd. As an ambassador for her species, she was always in demand for presentations and pictures, but probably the most significant occasion was when she was featured in the Life Magazine Year in Pictures for 1990. The picture of her sitting on the broad shoulder of a tough old logger named Wilbur Heath was truly worth a thousand words in terms of capturing the tension between the constantly growing human population and the needs of the other animals that inhabit our planet.

When she was about 25 years old, Fat Broad began to show noticeable signs of old age, and gradually became totally blind. During the last years of her life, Eric rarely took her out to public meetings because she was so old and frail that such occasions made her tired and grumpy. In her waning years, she spent most of her time just sitting around, eating mice, and waiting for somebody to come home and talk to her or give her a scratch on the head. In February 2002, Fat Broad stopped eating and just sat around with her eyes closed, looking really tired. It became obvious that no amount of doctoring was going to make any difference. On her last day of life Eric found her laying on one of her perches, too weak to move. He went to work, but very soon returned home, unable to concentrate and expecting the worst. She was still squatting in the same place, barely breathing. He picked her up and held her in his lap and said "Hey old girl, I guess this is about it, huh?" She was so weak she couldn't even raise her head to talk to Eric like she usually did. She just lay there taking long shallow breaths that gradually slowed, and then stopped, leaving a gaping hole in one Spotted Owl biologist's heart. She would have been 32 that April.

Fat Broad was buried in the woods on the hill above Eric's house, facing the Coast Range Mountains, where her kind is still struggling to survive in the face of constant encroachment by humans and the threat of displacement by Barred Owls. Although just a single owl, Fat Broad played a huge role in Eric's life and research and touched the lives of untold thousands of people who met her.

Due to the owlet's tendency toward overeating and obesity, one of Eric's friends commented one day "She looks just like the character they call Fat Broad in the BC comic strip". The name stuck, and the political incorrectness of her name never bothered her.

Fat Broad rapidly became part of Eric's family, as well as an important source of information on the biology of the Spotted Owl. She lived in a large cage beside the Forsman house, and for years Eric kept notes on her molt and her behavior. These observations led Eric to publish papers on the molt, behavior, and nesting chronology of the Spotted Owl. But much more importantly, she traveled with Eric to numerous public presentations and visits to schools when he gave talks about Spotted Owls and old forests. At these talks Eric frequently let her loose to roam around the room. She was a great addition to the programs because regardless of whether Eric gave a good presentation or not, people in the audience were always in awe of the beautiful brown owl that was completely at ease in the middle of the crowd. As an ambassador for her species, she was always in demand for presentations and pictures, but probably the most significant occasion was when she was featured in the Life Magazine Year in Pictures for 1990. The picture of her sitting on the broad shoulder of a tough old logger named Wilbur Heath was truly worth a thousand words in terms of capturing the tension between the constantly growing human population and the needs of the other animals that inhabit our planet.

When she was about 25 years old, Fat Broad began to show noticeable signs of old age, and gradually became totally blind. During the last years of her life, Eric rarely took her out to public meetings because she was so old and frail that such occasions made her tired and grumpy. In her waning years, she spent most of her time just sitting around, eating mice, and waiting for somebody to come home and talk to her or give her a scratch on the head. In February 2002, Fat Broad stopped eating and just sat around with her eyes closed, looking really tired. It became obvious that no amount of doctoring was going to make any difference. On her last day of life Eric found her laying on one of her perches, too weak to move. He went to work, but very soon returned home, unable to concentrate and expecting the worst. She was still squatting in the same place, barely breathing. He picked her up and held her in his lap and said "Hey old girl, I guess this is about it, huh?" She was so weak she couldn't even raise her head to talk to Eric like she usually did. She just lay there taking long shallow breaths that gradually slowed, and then stopped, leaving a gaping hole in one Spotted Owl biologist's heart. She would have been 32 that April.

Fat Broad was buried in the woods on the hill above Eric's house, facing the Coast Range Mountains, where her kind is still struggling to survive in the face of constant encroachment by humans and the threat of displacement by Barred Owls. Although just a single owl, Fat Broad played a huge role in Eric's life and research and touched the lives of untold thousands of people who met her.

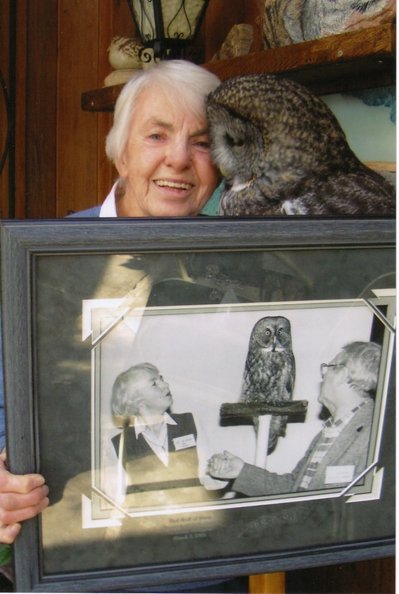

"The Owl Lady of Canada," "The Grande Dame of Owls," and "The Jane Goodall of Owls" are all phrases that have been aptly used to describe Katherine (Kay) McKeever, the founder and president of The Owl Foundation in Vineland, Ontario, Canada.

Although strongly wildlife-orientated as a child and teenager, after high school Kay joined the Canadian Air Force during the 1939-45 war. She served on the Pacific coast until 1945, then worked for an air survey organization in Ontario, where she got her pilot's license. Following this she married, had two children and lived in Brazil and Argentina for 6 years. It was not until she was 38, divorced and had designed several houses that she built her own house in the Niagara Peninsula where she has lived ever since. There, with her young son, she began a hands-on experience with traumatized local wildlife. A juvenile Screech Owl from the Humane Society in 1965 was her first owl. The poor owlet died but an investigation of the reasons began a 40-year involvement with owls, from rehabilitation through behaviour, breeding and architectural cage design.

Kay's early efforts focused on owl rehabilitation, and thus the Owl Rehabilitation Research Foundation was born at her home in Vineland, Ontario. Through trial and error and with the help of several gifted veterinarians, Kay developed many successful techniques for returning owls to the wild. These were compiled into a manual titled "Care and Rehabilitation of Injured Owls," which has become known as the bible of owl rehabilitation and is now in the second printing of the fourth edition. To date it has sold close to 8,000 copies in nearly 30 countries around the world.

Later, when faced with so many unreleasable but otherwise healthy owls, several of uncommon species, Kay's later efforts turned to recycling the genes of these damaged owls. She began a program to breed permanently injured owls and return their progeny to the wild. This involved developing innovative new cage designs that allowed the owls to make choices about mates, visibility, and more. This came naturally to Kay, who also happens to be a self-taught architect. Her cage designs have become the ideal that facilities strive to achieve.

The breeding project also led to the installation of remote cameras in the owl cages to monitor pair bonding and mating behaviour. With thousands of hours of footage of owls that have no idea they are being observed, Kay has become a treasure trove of information about intimate owl behaviour.

Kay's unique sense of humour, tell-it-like-it-is personality, and vast experience have led her to become a much sought-after speaker for hundreds of meeting across North America over the years. Her efforts have also been recognized with innumerable awards, including honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from two Universities and even the Order of Canada, the highest Canadian civilian honour possible.

Kay's life is now entirely dedicated to owls, and has been for most of the 40+ years since receiving that first Screech Owl. The Owl Rehabilitation Research Foundation has evolved into The Owl Foundation, where Kay spends her days (and nights!) fielding phone calls from rehabilitators, researchers, and others seeking information about owls from around the globe; overseeing the care of nearly 200 resident owls at The Owl Foundation; and trying to find time to put her wealth of knowledge down on paper.

Although strongly wildlife-orientated as a child and teenager, after high school Kay joined the Canadian Air Force during the 1939-45 war. She served on the Pacific coast until 1945, then worked for an air survey organization in Ontario, where she got her pilot's license. Following this she married, had two children and lived in Brazil and Argentina for 6 years. It was not until she was 38, divorced and had designed several houses that she built her own house in the Niagara Peninsula where she has lived ever since. There, with her young son, she began a hands-on experience with traumatized local wildlife. A juvenile Screech Owl from the Humane Society in 1965 was her first owl. The poor owlet died but an investigation of the reasons began a 40-year involvement with owls, from rehabilitation through behaviour, breeding and architectural cage design.

Kay's early efforts focused on owl rehabilitation, and thus the Owl Rehabilitation Research Foundation was born at her home in Vineland, Ontario. Through trial and error and with the help of several gifted veterinarians, Kay developed many successful techniques for returning owls to the wild. These were compiled into a manual titled "Care and Rehabilitation of Injured Owls," which has become known as the bible of owl rehabilitation and is now in the second printing of the fourth edition. To date it has sold close to 8,000 copies in nearly 30 countries around the world.

Later, when faced with so many unreleasable but otherwise healthy owls, several of uncommon species, Kay's later efforts turned to recycling the genes of these damaged owls. She began a program to breed permanently injured owls and return their progeny to the wild. This involved developing innovative new cage designs that allowed the owls to make choices about mates, visibility, and more. This came naturally to Kay, who also happens to be a self-taught architect. Her cage designs have become the ideal that facilities strive to achieve.

The breeding project also led to the installation of remote cameras in the owl cages to monitor pair bonding and mating behaviour. With thousands of hours of footage of owls that have no idea they are being observed, Kay has become a treasure trove of information about intimate owl behaviour.

Kay's unique sense of humour, tell-it-like-it-is personality, and vast experience have led her to become a much sought-after speaker for hundreds of meeting across North America over the years. Her efforts have also been recognized with innumerable awards, including honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from two Universities and even the Order of Canada, the highest Canadian civilian honour possible.

Kay's life is now entirely dedicated to owls, and has been for most of the 40+ years since receiving that first Screech Owl. The Owl Rehabilitation Research Foundation has evolved into The Owl Foundation, where Kay spends her days (and nights!) fielding phone calls from rehabilitators, researchers, and others seeking information about owls from around the globe; overseeing the care of nearly 200 resident owls at The Owl Foundation; and trying to find time to put her wealth of knowledge down on paper.

Naturalist, ornithologist, avocational archaeologist, poet, and a well-known scientist with nearly 500 publications and 9 books to his credit, Dr. Robert (Bob) Nero is perhaps best known for his pioneering research on the Great Gray Owl.

Born and raised in Wisconsin, Bob served a stint in the military during World War II, then earned his PhD researching Red-winged Blackbirds under John T. Emlen, while also studying under the likes of J. J. Hickey and Aldo Leopold.

Employment eventually led Bob to Canada, where he has lived for over 50 years. He has worked for the Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History, the University of Saskatchewan at Regina, the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, and Manitoba Conservation. He still holds the title of Volunteer Senior Ecologist with Manitoba Conservation.

Bob began his pioneering work on Great Gray Owls in the 1960s when little was known of this elusive species. His Smithsonian Institution Press book "Great Gray Owl: Phantom of the Northern Forest" quickly became a classic, in part due to Bob's unique twin talents as both a scientist and a poet.

But one very special Great Gray Owl helped Bob gain new insights into the species and played a significant role in his life for over 21 years. In 1984 Bob rescued an owlet from certain death as the runt of her brood. This owlet grew up to be known as Lady Gray'l, and together she and Bob taught thousands of school children about owls and raised money for graduate research and wildlife rehabilitation. Lady Gray'l also gave Bob insights into the behavior and molt patterns of her species. As a direct result of their efforts, the Great Gray Owl was named the provincial bird emblem of Manitoba on July 16, 1987.

Besides researching Great Gray Owls, Bob helped develop management plans for Barn, Burrowing, and Great Gray Owls. Over the years he has studied eleven species of owls, and worked diligently to organize two international owl symposia.

Bob has received numerous awards from a plethora of organizations over the years including the Manitoba Naturalists Society, Saskatchewan Natural History Society, Ottawa Field-Naturalists' Club, The Wildlife Society, and the highest award possible from the Society of Canadian Ornithologists, the Doris Huestis Speirs Award.

In his most recent book, "Growing Old Together," Bob pays tribute to his wife Ruth through a collection of poetry. She has stuck with him through thick and through thin, always encouraging Bob to write and pursue his interests, and for 21 years sharing him with Lady Gray'l. Her unfailing support is behind Bob's talent for making this world a better place for owls.

Born and raised in Wisconsin, Bob served a stint in the military during World War II, then earned his PhD researching Red-winged Blackbirds under John T. Emlen, while also studying under the likes of J. J. Hickey and Aldo Leopold.

Employment eventually led Bob to Canada, where he has lived for over 50 years. He has worked for the Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History, the University of Saskatchewan at Regina, the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, and Manitoba Conservation. He still holds the title of Volunteer Senior Ecologist with Manitoba Conservation.

Bob began his pioneering work on Great Gray Owls in the 1960s when little was known of this elusive species. His Smithsonian Institution Press book "Great Gray Owl: Phantom of the Northern Forest" quickly became a classic, in part due to Bob's unique twin talents as both a scientist and a poet.

But one very special Great Gray Owl helped Bob gain new insights into the species and played a significant role in his life for over 21 years. In 1984 Bob rescued an owlet from certain death as the runt of her brood. This owlet grew up to be known as Lady Gray'l, and together she and Bob taught thousands of school children about owls and raised money for graduate research and wildlife rehabilitation. Lady Gray'l also gave Bob insights into the behavior and molt patterns of her species. As a direct result of their efforts, the Great Gray Owl was named the provincial bird emblem of Manitoba on July 16, 1987.

Besides researching Great Gray Owls, Bob helped develop management plans for Barn, Burrowing, and Great Gray Owls. Over the years he has studied eleven species of owls, and worked diligently to organize two international owl symposia.

Bob has received numerous awards from a plethora of organizations over the years including the Manitoba Naturalists Society, Saskatchewan Natural History Society, Ottawa Field-Naturalists' Club, The Wildlife Society, and the highest award possible from the Society of Canadian Ornithologists, the Doris Huestis Speirs Award.

In his most recent book, "Growing Old Together," Bob pays tribute to his wife Ruth through a collection of poetry. She has stuck with him through thick and through thin, always encouraging Bob to write and pursue his interests, and for 21 years sharing him with Lady Gray'l. Her unfailing support is behind Bob's talent for making this world a better place for owls.

|

The International Festival of Owls is a fundraiser for the International Owl Center and the Center’s biggest event of the year.

|